This page is an automated translation of /nl/atlanticcrossing2.html and is awaiting a manual review.

We have been monitoring weather conditions between the Cape Verde Islands and "the other side" of the ocean for quite some time. It is monotony that strikes the clock: the wind is all the way to the West and always with 15 to 20 knots of wind. Here the famous "trade wind" (or "trade wind") blows, an air current parallel to the equator that moves steadily from East to West throughout the winter. At least in theory. But as far as we can see from the weather data, the trade wind is a fact. The great Atlantic rally (ARC) started a few days ago, but there are also numerous ships sailing that make the crossing on an individual basis. We check the weather data again, but they still look good. Actually, it's only about the first few days, because a forecast for two weeks is not very valuable anyway. We drop anchor in the morning without much ado and we are on our way.

Originally we planned to visit several Cape Verde islands, but we discover that we prefer to stay somewhere longer and then visit fewer destinations. It gives more peace and a little more opportunity to get to know the people and the environment better.

Day Suriname

Our destination is Suriname. It is one of the closest destinations to Cape Verde and we have read many enthusiastic blogs from other travelers. Now that we already have some sailing time, we continue reading. There is a lot of culture, you can sail up the river and swim in the muddy water, you can go deep into the jungle, but it is wise to take Malaria pills. Yeah. Given our itinerary, we only want to stay there for a short time. But we don't really feel like culture right now, we long for crystal clear water in which we can snorkel and we don't really like the Malaria story. To be sure, we read through the information we have about the Caribbean again and we now find that much more attractive. Sailing to the Caribbean does mean a few days extra. But on the other hand, it is four days sailing from Suriname to the Caribbean, so net we save sailing days, plus the stay in Suriname. And had we not just discovered that we would rather stay a little longer in fewer places than shorter in more places? Some will call us crazy, but we will remove Suriname from the program for now and adjust the course a few degrees to end up in the Caribbean. If the rest of the journey goes as we now think, it is also much more logical to visit Suriname in the second part of the journey; rounding the Cape of Good Hope and crossing the island of St. Helena to Brazil we pass it on the way north. And that's the beauty of this way of traveling: You can just change course and change the destination if you feel like it.

Exciting

Whether it's not exciting to cross the ocean?

On the one hand, that sailing is very relaxing. Softly swaying on the waves, moving motorlessly, with the same view all around you that does not seem to change. No internet or other disturbing elements. Staring at the waves crashing into the back of the boat has just as much of an effect as staring into the flames of a wood stove.

But on the other hand, like the fire in the fireplace, the whole thing has the potential to get completely out of hand. The bucket of water should be next to the fireplace, and as you cross the ocean you should be constantly aware that things could break, that the weather could suddenly change, that someone could get sick, and so on.

Especially at night when there is no moonlight it feels exciting. You sit there by yourself, the wind is slowly swelling, you hear waves breaking next to the boat, sometimes giving a hard blow to the hull, but you don't see the waves. Only when they burst into foam do you see the foam, because it lights up because of the luminous plankton that gives light signals during violent movement. But actually it is much more exciting to lie in bed and just hear all the sounds without looking at the instruments and sails and seeing what is happening. You lie in the dark bed while the sea - shielded with only 6-8 mm aluminum - rushes and swirls beneath you. It is unbelievable how roaring the sea and the wind can sound, especially when the waves are high and smash against the ship or break under you. You cannot help it to ask the other now and then: are we going well, are we not going too fast ...?

The elements that provide tension:

- Weather

- In principle, we can handle fairly extreme weather, provided it does not present itself as a complete surprise. So we closely monitor the weather, simply by observing the sky, by downloading grib files, by communicating with fellow sailors and by downloading weather faxes. Still, it remains exciting because the meteorologists have fewer monitoring stations on the ocean than on shore and the weather forecast on the ocean can therefore be taken with a grain of salt. We always test the predicted wind direction, air pressure, etc. against our own observations and if those things start to deviate in an inexplicable way, then that is a "point of attention".

- Defects

- Things that can break also always pose a threat in the background. We keep a close eye on everything. Everything that vibrates, flaps, rubs, etc. is hard to break so you always listen and feel whether everything is at rest and if it is not then you have to do something about it. Prevention is better than cure. It goes without saying that we have checked the boat carefully before crossing and that everything is well maintained. And that we have a backup for all critical components. Yet you already know in advance that it is inevitable that things will break and that you have to improvise. Fortunately, not much breaks during the trip. Only a zipper runner of the jib's sail cover, deck light, and small parts from both autopilots fail. For the first two defects, we come up with a backup, the last two defects are creatively repaired. It is said that it is more important for a crossing to be able to repair things independently than to be able to sail well. We think there is a lot to be said for that statement.

- Collisions

- Then there are the objects you may encounter: other boats, weather buoys, and the "inevitable" category such as half-sunken containers and sleeping whales. The chance of the latter two is very small, about the same as on shore by a falling meteorite or being hit by lightning, but still. And for the other boats and static objects such as weather buoys, we rely on our equipment, such as the AIS, radar and GPS.

- Crew

- If you fall ill or are injured here, there are two major problems: You are 1000 kilometers from the nearest hospital and with a two-man crew you do not have much reserve of manpower and the loss of half of the crew is a disaster. Of course there are solo sailors, but the boat is equipped for that. We therefore keep a close eye on the health of the crew, do not eat questionable products and pay extra attention to everything we do. And we are kept on a leash at night and sometimes also during the day so that we cannot simply disappear from board. We do not drink alcohol, take sufficient rest and ensure that we can be constantly alert.

For your reassurance: In the unlikely event that things go badly wrong, we have the necessary backup: We can request medical assistance via satellite (diverting a cruise ship with an operating room if necessary), we have a survival raft, floating radio transmitter that can sends out an emergency signal with our GPS position, etc. But of course we don't want to have to use that at all.

In short, it is calming on the one hand, but on the other it remains exciting, we count down the miles until we get to the other side, and have a party with relief when we make it.

Time

We use different times on board. That's confusing enough for us, let alone the readers of this story. So here is an explanation.

- Solar time

- This is the actual time, according to the definition that the sun is at its highest point at noon. Solar time is different at every place on the earth because the earth simply revolves and a different part of the earth is always pointed exactly towards the sun.

- Local time

- This is the time that is observed in the country concerned. Usually this is the solar time, rounded to a whole hour, but often a different time is used because this is better suited to the neighboring countries. Strictly speaking, the Netherlands should have the same time as in England, but it is more practical to keep the same time as the rest of the European mainland.

- Summertime

- To make it even more complicated, some countries also do summer time so that the relationship with solar time is completely lost. Not all countries use daylight saving time, so sometimes there is and sometimes no time difference. And summer time is set in the southern hemisphere when it is winter in the Netherlands.

- Board time

- This is the time we keep on the boat. Normally that is the local time, but in the middle of the ocean there is a different time zone every 15 degrees west longitude. This is because the Earth is divided into 360 degrees, and since the Earth revolves in 24 hours, there are 24 time zones of 15 degrees each. Of course it doesn't matter much on board because we don't have any appointments anyway, but for our waiting schedule it is nice if the time before and after midnight contains just as much "dark". And it is useful on arrival if you have already gotten used to the local time.

- UTC

- UTC is a time that is the same all over the world. No time zones, no winter or summer time. A beacon in the confusion of time. On board we have the necessary clocks on UTC, which is useful to know when a particular broadcast starts on the radio (which is wisely specified in UTC), to measure the length of time we are on the way (even if we pass several time zones and we adjust the ship's time in the meantime), and in our cameras and logbooks so that we do not have to wonder later on whose local time something was recorded. UTC is one hour behind Dutch local time, or two hours when it is summer time in the Netherlands. While writing this article we are in the Caribbean where they use the time zone UTC-4, so our time is 5 hours behind the Dutch winter time.

Daily activities

Normally the day starts with getting up, but not with us. "We" don't get up at all, because when one of us goes to bed the other gets up. There is no real start to the day, so let's consider midnight as the start of the new day. Although that midnight is also debatable, because we travel after the sun and "midnight" is every day 10 minutes later and a few times we set the clock back one hour to get the board time back to the solar time.

My watch officially ended at midnight. In practice it often becomes 01:00 am because Ilona sometimes delays a bit before going to bed and if I am not terribly sleepy at midnight, I would like to give Ilona that extra hour of rest. We change the guard quickly and efficiently, usually there is not much to say and everything is the same as six hours ago. It is a pity that it is so hot because otherwise I would definitely have enjoyed getting into a preheated bed. I often wake up to the sounds and movements of the boat. Usually it is still dark then but when I see that it happens to be light then I get up. It is also not possible to lie down too long because we have a busy morning program.

Our eating habits are quite different than at home. We eat "strange" local things, but our menu is necessarily different on board than at home. I think it's all fine, but my traditional Dutch breakfast is non-negotiable. I just want a cheese sandwich, period, and that includes a cup of tea. But it already starts with the tea: how are we going to make it? We can do this with an electric kettle but also with the help of a whistling kettle on our gimbal stove. The preference is for the electric kettle: environmentally friendly because the electricity comes from our solar panels and therefore does not cost fossil fuels. Easy too, because there is nothing more annoying than having to look for gas cylinders in another country. Everywhere they have different connections, different rules, and gas is not readily available everywhere, not to mention the hassle of finally getting the gas bottle on board from the depot. The electric kettle is therefore a favorite, but sometimes it is cloudy and the solar panels deliver less, or we expect to have to use a lot of electricity for other things. So first of all we have to look at the flow situation and only then can we determine how to make tea. We usually use the electric kettle and make two liters of tea that we pour directly into thermos so that we can use it all day long.

We don't get to breakfast just yet, because there are some decisions we have to make first. Should sail be added or removed? Fresh weather data is crucial for this and we need to get it via shortwave, via connections to stations thousands of miles away. That is not easy, it depends on many factors, including time: morning and evening works best, around noon there is usually no contact with any station. And a station can only communicate with one ship at a time, so often the usable frequencies are occupied. I compose an email containing the coordinates of the area from which I want weather information, the type of information, the resolution and some other parameters. I then send that email via shortwave to an automated station where they package the data for us in an attachment that is sent back to us. Email is painfully slow: 7kb per minute is the fastest I've ever seen, but 500 bytes per minute is usually the norm. That is why we first ask for a minimum of data, compare that data with the forecasts of the previous day, and if there are unexpected changes or the situation gives cause to do so, we compose a new email in which we request additional data. This means that the connection usually has to be established four times to obtain the weather data alone.

In a table I can look up which radio stations on which frequencies could in principle be reachable. Whether they are really accessible depends on the atmospheric situation. During our crossing I had good results with a radio station in Canada (Halifax), but connections are also regularly made with Europe and South and North America. The entire email ritual easily takes an hour or more. The cherished grib files are loaded into a program after receipt, after which we can see what the expected wind strength and direction are. You have to take the data with a grain of salt (of which we have enough here) but it is a nice indication.

Often we do not have to adjust the sail lining, but sometimes the wind has subsided a bit during the night and if the grib files indicate that the wind will not pick up again, then sail must be added. Or the other way around of course.

Breakfast is a lot of juggling with plates, bread and spreads. Nothing stays put by itself. If you have your plate sliding on the counter, it is again the bread that slides off your plate before you can get the butter. And you will be short of arms because you have to hold the plate, the butter, your knife, the bread at the same time and oh yes, yourself too. If you carefully slide open the cupboard, not only the nutella but also the peanut butter will come out. Except for the one day when the jar of peanut butter was broken and therefore stuck neatly in the cupboard. The Nutella is liquid in this climate, so you have to be careful when opening it.

After breakfast it is quiet for a while and Ilona often takes the opportunity to get some sleep.

It takes us a day and a half with homemade bread, so sometimes we have to bake bread for breakfast and sometimes for lunch. Fortunately, we have a very luxurious bread maker for that, but you should of course not forget to fill the device and unfortunately it happens that someone has forgotten to start the thing ... Well forgot, the kneading of the dough is a bit noisy so preferably we only switch on the device when no one is sleeping. But then you still have to remember to press the button later ... Luckily we also have cookies!

After lunch I can go to sleep. I don't always sleep, but it is nice to have a moment of rest. Because after dinner I have to wait and then I have to be fit. Just before dinner it is time to download the weather data again, and that ritual again takes a lot of time. The weather data is important to be able to assess what we are going to do with the sail lining at night. We prefer not to make any changes at night, so if we think that the wind will increase, we will already put in an extra reef. Or if we know that the wind direction is going to change, we will already set the sails in the right direction. In principle we have tailwind so the sails can be set to both sides, but in practice the wind is just not straight from behind and then it is better that we set the sails in the best way.

Dinner is always a surprise despite the somewhat limiting circumstances. We even eat a real pizza once!

After dinner it gets dark and Ilona goes straight to bed. It is my watch then and generally such a watch is quite boring. Until there are strong winds or we are colliding with some tanker or cargo ship. We always thought that it would be so relaxing to pilot a ship instead of an airplane, because in conflicting traffic you don't have to think in seconds, but you can safely take an hour for it, but in practice this hardly proves to be more soothing. to be. And we have conflicting traffic remarkably often during the first and last days of our crossing. You would think that such an ocean is big enough, but somehow we manage to cross the path with something big and logs.

Traffic!

I see a dot light up on our AIS. AIS is a system in which every ship transmits its position and other data via the radio so that you no longer need a radar to see other ships. The advantages are that it is unambiguous (radar sometimes misses a boat and sometimes makes up boats that are not there) and that you also immediately have all kinds of extra data such as the names and dimensions of the ships in the area. For example, I see a tanker of more than 300 meters in length sailing our way. Our navigation computer calculates precisely that the CPA (the "Closest Point of Approach") will take place in an hour and a half and that we will be only 100 meters apart. But because our speed changes a bit, as well as our course, and the same goes for the other ship, this number is constantly being adjusted. Sometimes we don't get closer than 2 miles according to the calculation, but sometimes that distance is only 20 meters.

Ilona has only just got to bed so I call in that we have exactly managed to cross the path with a fat tanker. Ilona is watching her mobile phone, which can display the navigation data by means of a clever app and she can now also see the tanker. The tanker is coming exactly from the right but has no right of way. Because the rule is simply that sailing boats have the right of way over motor boats, and a tanker is a motor boat, even if it is a bit big. So I expect (or hope) that the tanker will do "something" about the situation, but nothing happens. We are not going to do anything about it ourselves now because the sails and autopilot are just perfectly set for the night and Ilona is already in bed. A small change of course will not solve this situation and for a drastic change of course the sails have to be adjusted again, but both crew members must be present.

After half an hour the situation has not changed and we are still on collision course. I let my eyes get used to the dark again and peer in the specified direction. Indeed, I now see a light there far away, so damn it is already coming. At one point I see the tanker turning a few degrees to the east, so it passes behind us. On the computer, the CPA instantly turns into a comforting 3 miles. But a few seconds later the wind drops a bit and our speed also drops. So by the time the tanker would pass us behind, we will not be out of there yet and the computer will punish us right away with a CPA of only ten meters. The tanker now turns slightly to the west again, and we keep playing cat and mouse. Minutes pass but nothing changes. We can't really do much, because our speed is determined by the wind. We can steer a little to the right or left, but because the tanker is approaching us at right angles, this only means that the collision will take place a little earlier or later.

With only half an hour to go, I am fed up and call the tanker. He sails under the Greek flag and, as I thought, communication is difficult. "Good evening, this is sailing yacht Omweg. It appears to us that we are on a collision course. What are your intentions?" Something unintelligible returns. I try a bit more direct: "We are a sailing yacht and somewhat limited in maneuvering. Can you pass behind us?" Something comes back that looks like agreement to this plan, but nothing happens. So I ask very directly: "Would it be possible that you change your course a little bit to the east?" "Ok" comes back, and indeed I see on the computer that the tanker is slowly starting to turn. The CPA now changes back to a healthy 2 miles. The wind is also picking up a bit, which means we are going to sail faster and should have a larger gap, but the CPA does not increase further. On the computer I see that the Greek tanker immediately consumes any space gain by turning back to its original course. Well, he is right, of course, because it will cost a bit to let such a tanker sail a detour because of the sailing boat Omweg, and in principle 2 miles in between is enough. I just hope those Greeks understand that our speed can fall back just as easily and that they have to dodge again. But luckily all goes well and the tanker eventually passes us with the planned 2 miles gap behind. The whole ritual demanded my attention for an hour and a half, kept Ilona awake, and all in all disrupted the peace on board. What better than to see a Boeing approaching you on our plane? The latter is usually dealt with in a few seconds and in any case does not take a nerve-racking hour and a half ...

Highlights

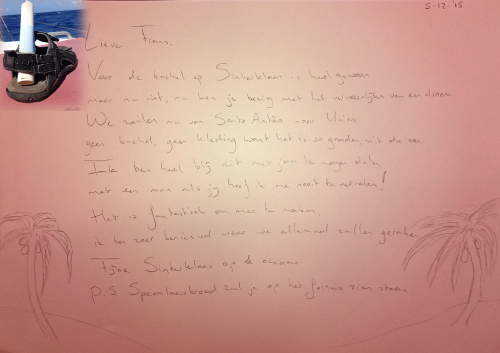

- Saint Nicholas

- At Sinterklaas I suddenly see a shoe, my shoe, on the floor of the cockpit! The surprise is all the greater because I haven't seen any footwear for weeks. And in the shoe is a poem! And Ilona has been creative in the galley and baked gingerbread bread. Without gingerbread spices, but on the gamble of what individual ingredients belong in. And the result indeed looks surprisingly good on speculaas! Mum!

- Race catamaran

- I see something strange on the AIS. During a crossing, hardly any other traffic is visible on the AIS, so the occasional time we see a boat on the screen, we look interested in what is sailing there. The AIS says it is a sailing vessel, but the speed is no less than 32 knots! And that is terribly fast for a sailing boat. I can deduce from the dimensions that it must be a catamaran or trimaran. At such a speed, an Atlantic crossing only takes 3 days! So it must be such a hi-tech carbon fiber-like prestige colossus that you sometimes see at trade fairs. A while later we actually get to see it and see it tearing past on the horizon.

- Blue Marlin

- On the penultimate day of the crossing, it looks like we will be arriving at Union Island too early. We sail with maximum reef just a little too fast, so we consider taking a swimming break. So just stop the boat and go for a swim one by one. While we are talking about it, I suddenly see another shadow whizzing through the water next to Omweg. We often see that, and until now they have always been dolphins. But this "dolphin" is very big, almost 3 meters long we estimate, and on its own. And it has a blue vertical tail that occasionally sticks out just above the water and cuts through the water like a knife. And a long pointed muzzle, and blue vertical stripes on its body. It turns out to be a Blue Marlin! A fish that every fisherman hopes to catch, but now he just swims around our boat and we have no intention of catching this beautiful animal. He keeps swimming around the boat for a long time and he is more beautiful than we see (later) on photos on the internet. It is one of the largest fish out there and can weigh up to 1000 kilos. And they use their pointed snouts as a weapon with which they injure prey so that they can eat it later. Fortunately, the wind drops a bit so that we don't have too much time and we no longer have to wonder whether or not we want to swim a bit with a Blue Marlin.

- Arrival

- The morning of our arrival, the sky is more threatening than we have seen during the entire crossing. Bad weather seems to be on the way. Will you just see, the whole crossing is fine weather, and then during one of the last hours stormy weather? Fortunately it remains with a threatening sky and some time later we still walk into the anchorage. But once properly anchored, a huge tropical rain shower will erupt! Welcome to the Caribbean! It takes some time before we realize that the crossing is over. We really did! An Atlantic Crossing!

Statistics

- Distance traveled: 2,200 miles

- Duration: 17 days

- Average speed: 5.3 knots

- Number of hours driven: 6

- Wind: Usually between 15 and 25 knots, sometimes peaks up to 33 knots, the first days only 10 knots of wind

- Moon: We started with full moon all night long, but at the end of the crossing there was no moon left

- Temperature: 30 to 35 degrees during the day, 25 to 30 degrees at night. Sea water temperature about 28-29 degrees.

- Defects: Zipper of the sail cover jib. Electric autopilot extension rod. Mechanical autopilot control lines.